The US & China: Active Non-Alignment & the Future of the Indo-Pacific

This is a research article written in late 2024 on the overarching global theme of Active Non-Alignment in today’s political environment in the Info-Pacific. It includes recommendations for US national security policy and Transatlantic Relations.

Introduction

When votes for UN Resolution ES‑11/4, calling for Russia to "immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw" from Ukraine, were counted on October 12, 2022, 40 countries abstained or voted against the resolution.

This was less than the 2014 UN vote condemning the Russian annexation of Crimea (69 total abstentions and votes against). Still, the message was clear: many countries would not engage in another dispute between great powers.

The countries that abstained from the vote were a throwback to the Cold War: 85% were members of the Non-Aligned Movement, a group of countries committed to principled resistance to great power blocs.

Founded in 1961 (History, 2023), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is the second-largest grouping of states worldwide, with 121 members. In 2024, it accounted for about 60% of the United Nations' overall membership (Non-Aligned Movement—Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, n.d.).

Developed by Yugoslav leader Josip Tito in the 1950s, the movement’s origin directly responded to pressure and aggression from the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. (Rajak, 2014) Despite low levels of activity in the decades leading up to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, its large membership is an indicator of an increasingly multipolar world. One of the movement’s key features is abstention from any alignment with a great power bloc, which they categorize as unlike the neutrality demonstrated by Western nations, such as Finland, Sweden, Ireland, Austria, and Switzerland (none of which joined the NAM). (Turner, n.d.) The movement’s policy of non-alignment “represents the positive, active and constructive policy that, as its goal, has collective peace as the foundation of collective security.” (Rajak, 2014)

Regardless, the “politics of absence at the UN General Assembly” (Coggins & Morse, 2022) and other demonstrations of non-alignment with great powers have been studied for their implications for international relations.

“Absence can be a form of protest, disengagement, or a strategy for managing competing interests, ….[and] strategic absence is a way for weaker states to navigate competing geopolitical pressures.” (Coggins & Morse, 2022)

Today, Active Non-Alignment refers to “an aspirational policy that would promisingly guide the nations of the Global South … [through] Great Power competition” (Feeley, 2023). Though the level of coordination in this movement is unclear, the potential of this large group of states can’t be ignored.

The Global South’s active non-alignment in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine presents a new challenge for US foreign policy related to its security interests in Asia, where another ally faces a similar imperialist threat: Taiwan. If responses to Russia’s invasion signal future actions from the Global South, how should the US reconsider its foreign and defense policies concerning these countries?

This paper will explore the evolution of the Non-Aligned Movement and its resurgence in contemporary international politics and examine its influence on responses to the Ukraine conflict while considering its broader implications for Taiwan-China tensions and U.S. foreign policy.

Specifically, this paper will explore the following questions:

What are the implications of active non-alignment on the future of US foreign policy?

Considering the parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan, how could the US prepare for active non-alignment in the face of a similar conflict in the Indo-Pacific region?

Based on my analysis, this paper suggests that the Global South’s recent Active Non-Alignment in the face of Russian aggression indicates a likely repetition of cautious, interest-driven responses in a Taiwan scenario, which has significant implications for U.S. strategy.

I build off of existing research to recommend that the United States:

Develop a defense strategy and force posture capable of dealing with China and Russia simultaneously,

Develop the QUAD security alliance in the Indo-Pacific, specifically engaging with countries outside the NAM (Japan, Australia), and

Continue to engage NAM members through the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), formed by US President Biden in May 2022

Theoretical Framework: Active Non-Alignment

The Active Non-Alignment Movement evolved from the official Non-Aligned Movement, established in 1961. After Yugoslavia’s expulsion from the Soviet Union, Josip Tito sought allies in “active peaceful coexistence” (Rajak, 2014) to fend off potential aggression from the USSR. He found an ideological partner in Nehru, India’s first prime minister, with whom he laid the foundations for a formal alliance of member states that felt both fear of aggression and mistrust towards either great power.

“Tito insisted that the division of the world into blocs was, by its very nature, a danger for smaller countries and that the competition between the two blocs threatened their very existence.” (Rajak, 2014)

Beyond potential aggression from the USSR, Tito hoped to avoid the influence of the US on his country's socialist goals. In discussions with Nehru, Tito also “ warned of China’s emerging role. He argued that, as a big country, China inevitably had its interests that it wished to pursue and attain.” (Rajak, 2014)

This resistance to military influence from great power blocs was ultimately represented in the requirements for membership in the movement (NAM Members and Observers, n.d.):

A Country should not be a member of a multilateral military alliance concluded in the context of great power conflicts.

If a Country has a bilateral military agreement with a great power or it is a member of a regional defense pact, the agreement or pact should not have been concluded deliberately in the context of great power conflicts.

If the Country has granted military bases to a foreign power, the concession should have not been made in the context of great power conflicts.

This philosophy resonated with the movement's other founding members, including many newly formed countries, especially in the Global South.

Influential founding members at the first NAM Conference in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, in 1961: Jawaharlal Nehru (India), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Sukarno (Indonesia), Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia) [Source: LotusArise, 2023]

25 founding member states of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. [Source: LotusArise, 2023]

However, while the NAM's focus began with resistance to military entanglement, members of the movement have interpreted this philosophy broadly in recent years.

Only a select number of NAM members have consistently used silence on the international stage to demonstrate non-alignment, indicating a potential lack of coordination. For example, in response to Russia’s repeated violation of sovereignty, only 36 of the 40 votes Against (or Abstained) UN Resolution ES-11/4 came from NAM members.

UN Resolution ES - 11/4 Voting Results [Data collected by author on November 1, 2024]

Of those who refused to condemn Russia’s violation of sovereignty, NAM members such as India, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Uganda also refused to halt trade with Russia by not joining US sanctions.

Some took these actions even further: after he met with Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni described Moscow as a “partner” in the struggle against colonialism going back a century. (Kifukwe, 2022) India also surpassed China as the top purchaser of Russian oil after the start of the conflict in Ukraine, exploiting their lack of participation in sanctions. (Verma, 2024) As the world's third-biggest oil consumer and importer, India has become the biggest exporter of oil products to the EU, further undermining Western efforts to limit Moscow’s revenue. (“Russian Oil Finds Its Way to Europe via India; India Now Biggest Exporter of Fuel to EU,” 2024)

The Global South's primary concern for economic development often supersedes political alignments, reflecting a modern manifestation of non-alignment policies rooted in economic self-interest.

Members of the Non-Aligned Movement in 2024 Demonstrate a Strong Representation of Global South Countries [Source: World Data, Accessed: 2024]

Rajak notes that economic development has historically been seen as “a prerequisite for a Third World country to achieve true sovereignty” (Rajak, 2014). This focus persists today, as many Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) members prioritize participation in non-Western economic alliances such as BRICS and the G77, seeking to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar and create alternatives in the global financial system. Brazil, for example, balances its relationships with the West while supporting BRICS initiatives and maintaining ties with Russia. Similarly, economic interdependencies, such as energy supplies, trade agreements, and infrastructure projects like China’s Belt and Road Initiative, heavily influence the Global South’s diplomatic strategies. These nations often reject U.S.-led sanctions, which they argue disrupt the global economy and harm their economic stability, underscoring their preference to avoid alignment with actions that could undermine growth and security. This economic pragmatism illustrates the enduring relevance of non-alignment in shaping the priorities of the Global South in international relations today.

U.S.-China Security Context

Another Great Power Rivalry

The U.S.-China rivalry represents a defining feature of contemporary global politics, as “Russia in many respects is a declining power lacking the economic dynamism to sustain its political punch,” China’s ascent is marked by “increasing economic, military, and diplomatic might” (Dar & Haasan, 2023). This dynamic has locked the U.S. and China into “what can only be called a new Cold War—an intense security competition that touches on every dimension of their relationship” (Dar & Hassan, 2023).

As the U.S. pursues its vision of a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” China’s “aggressive and expansive regional and global outlook” combined with “the lack of mutual trust underscores why the two powers are on a collision course” (Dar & Hassan, 2023). This intensifying rivalry places China as the “most dangerous player on earth,” a description by Graham Allison that highlights its role as a formidable challenger to the U.S. and the post-World War II international order in the Indo-Pacific (Allison, 2017).

Moreover, China’s motivation to unify Taiwan stems not only from a desire to bolster “the nationalist credentials of its leaders” but also to enhance “its military prowess in the region and beyond” (Dar & Hassan, 2023).

Security Context & Current Threat

The Indo-Pacific region represents a new epicenter of 21st-century global security challenges, with Taiwan emerging as the critical flashpoint in U.S.-China competition. Mearsheimer observes, "China is likely to be a more powerful competitor than the Soviet Union was in its prime," and this rivalry is "more likely to turn hot" in the Indo-Pacific, where global politics will be shaped for decades to come (Mearsheimer, 2021; Dar & Hassan, 2023).

Taiwan’s strategic location and its pivotal role in regional security make it the "most dangerous place on earth," with analysts warning that Chinese attempts to reunify Taiwan could rapidly escalate into a bloody war between the U.S. and China (The Economist, 2021; Allison, 2022). Chinese leaders have repeatedly stressed their commitment to reunification, with Xi Jinping warning he "would never promise to renounce the use of force" and Admiral Davidson predicting a potential invasion before 2027 (Indian Express, 2022; Davidson, 2021)

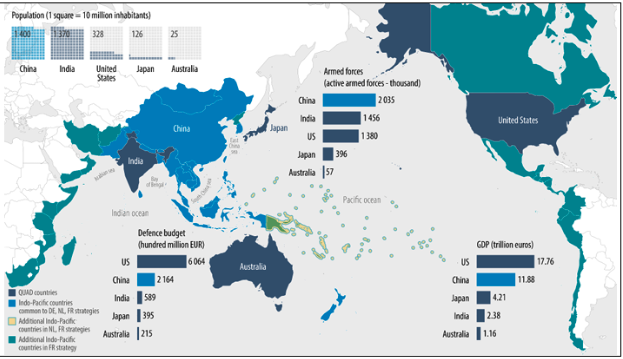

Map of the Indo-Pacific, as defined in strategies from France, Germany and the Netherlands. [Source: EPRS. Population, GDP and defence budget: 2019. Armed forces: 2020.]

For the U.S. and its allies, the unification of Taiwan would dramatically shift the regional military balance, granting China significant advantages through enhanced force structure, access to Taiwan’s deep-water ports, and the ability to project power far beyond the Indo-Pacific (Dar & Hassan, 2023). The stakes extend to QUAD, a grouping seen as a potential NATO-like alliance to deter Chinese aggression. QUAD, short for Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, was founded in 2004 after the Indian Ocean tsunami and currently includes four members: the US, India, Japan, and Australia. It has dealt broadly with security, economic, and health issues, operating largely informally. However, in recent years, members of QUAD have become more aligned on China’s increasingly assertive behavior. (Smith, 2021)

Taiwan is viewed as the "litmus test" for QUAD, with any hesitation in its defense risking a "China-centric regional order" and exposing severe vulnerabilities for key allies such as Japan, Australia, and India (Prakash, 2021). This would reduce these nations’ strategic autonomy and establish a Chinese Monroe Doctrine in Asia, leaving countries like Japan and India in constrained positions akin to Brazil and Argentina - “large countries that are nevertheless forced to live a constrained life” (Rajagopalan, 2021). The Indo-Pacific thus stands as a region where great-power rivalries, the security of Taiwan, and the future of the global order converge, with decisive actions shaping the balance of power for decades to come.

Strategic Implications of a Taiwan Scenario

Comparing Ukraine and Taiwan

The parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan in potential future conflicts highlight sovereignty challenges, major power rivalry, and critical economic interdependencies. Both cases involve the ambitions of neighboring powers—Russia in Ukraine and China in Taiwan—seeking territorial expansion under historical and strategic pretexts. Putin’s language regarding Ukraine reflects a justification for territorial annexation, akin to China’s view of Taiwan as a “protective barrier against foreign invaders” and a potential security threat if controlled by outside powers (Wachman, 2008). However, Taiwan's unique role as the global leader in semiconductor production, with the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) commanding “over half of the world’s market” (Hindustan Times, 2022), adds a significant economic dimension absent from Ukraine’s situation. This industry is critical to the U.S. economy, which cannot readily replace Taiwan's contributions, intensifying the stakes of a potential conflict.

China’s interest in Taiwan also mirrors Putin’s exploitation of perceived weaknesses among Western alliances, as demonstrated during the Crimea War. Putin capitalized on “transatlantic fissures vis-à-vis Russia” after observing limited resistance from Europe (Dar & Hasan). Similarly, “China’s obsession with Taiwan stems from its geographical location,” sitting just 80 miles from China’s coast and straddling key maritime regions, reinforcing its strategic importance (Wachman, 2008). Observers warn that Putin’s actions in Ukraine may embolden Xi Jinping to attempt similar moves in Taiwan, particularly as “China’s limited capacity to manufacture semiconductors” creates an incentive to monopolize the supply chain (Bosco, 2022; Schuman, 2022). As General Kenneth Wilsbach observed, China “would want to take advantage” of global preoccupation with the Ukraine crisis to pursue “provocative” actions in the Indo-Pacific (Panda, 2022). These dynamics suggest that Taiwan’s future conflict would involve sovereignty disputes, critical global economic repercussions, and heightened U.S. strategic commitments.

Case Study: India’s Likely Position

India, as a leading member of the Non-Aligned Movement, exemplifies active non-alignment through its pragmatic and often self-interested foreign policy. India abstained from condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequently exploited U.S. sanctions to become Russia’s top oil purchaser. In the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, India would likely repeat this pattern, abstaining from UNGA resolutions and refusing strict sanctions against China, prioritizing economic self-interest.

However, India would face significant economic shocks due to its proximity to China and subsequent disruptions to trade routes and semiconductor access in the event of a Chinese invasion. This would critically impact its information technology industry because, most notably, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone controls "over half of the world’s market," underscoring the potential economic fallout for India (Hindustan Times, 2022).

India’s geographic and security concerns add further complexity. Skirmishes along its border with China in 2020 and 2021 have heightened India’s wariness of its neighbor, with Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar noting that these clashes created "greater comfort levels" for intensifying national security collaboration with the U.S. and other partners (Rudd, 2021). These overlapping economic and security pressures could persuade India to play a more active role in QUAD as a security alliance. While this would align with India’s national interests and remain consistent with NAM principles, it would diverge from India’s recent responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The U.S. Perspective: Policy and Strategic Adjustments

In the case of Taiwan, the United States can draw many lessons from the Global South’s response to Ukraine. It should anticipate that many nations will abstain from overt support on the international stage, particularly in UNGA resolutions, and may prioritize non-aligned, self-interested economic decisions if sanctions against a great power are imposed.

Rivals like China could exploit these dynamics by courting NAM members with anti-U.S. rhetoric and invoking historical grievances tied to colonialism. To counter this, the U.S. should strengthen alliances by investing in the QUAD security framework in the Indo-Pacific and bolstering regional economic resilience through the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), particularly if India remains hesitant to join a security alliance. Furthermore, the U.S. must address perceptions of Western hypocrisy and double standards to foster broader coalitions and mitigate resistance from the Global South.

Conclusion

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) introduces complexity into modern international relations, particularly as great power rivalries intensify with nations like Russia and China. The U.S. and its allies face significant challenges in addressing inconsistent and self-interested foreign policy behaviors from NAM members, such as India. India’s responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, driven by ruthless self-interest, contradict NAM’s foundational principles and pose risks in future great power conflicts, including a potential "New Cold War" with China. In scenarios like the Taiwan conflict, India’s unaligned behavior is short-sighted, as it neglects the profound trade and supply chain disruptions that could cripple its economy. Unlike the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, today’s rivalries emphasize trade and digital technologies, demanding reliable relationships—a requirement incongruent with India’s current approach.

To address these challenges, the U.S. must prioritize aligning NAM members’ security concerns with their broader ambitions, emphasizing the strategic importance of alliances like QUAD and fostering regional economic resilience through initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), even if India opts out of QUAD. Future research should investigate NAM states’ actions during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to uncover their motivations. Still, it is clear that NAM, born out of a Cold War framework, may no longer be relevant in today’s interconnected, trade-driven conflicts. As global security challenges evolve, NAM members must reconsider whether their non-aligned actions genuinely serve their long-term goals.

Bibliography

Alden, C. (2023). The Global South and Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. LSE Public Policy Review.

Ann Marie Murphy (2017) Great Power Rivalries, Domestic Politics and Southeast Asian Foreign Policy: Exploring the Linkages, Asian Security, 13:3, 165-182, DOI: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1354566

Bellocchi, L.P. (2023). The Strategic Importance of Taiwan to the United States and Its Allies: Part Two – Policy since the Start of the Russia-Ukraine War. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters.

Chan, S.K. (2022). Precedent, Path Dependency, and Reasoning by Analogy. Asian Survey.

Chen, D.P. (2020), The End of Liberal Engagement with China and the New US–Taiwan Focus. Pacific Focus, 35: 397-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/pafo.12176

Dar, A.I., & Hassan, Y.U. (2023). USA, QUAD and China’s Inevitable Taiwan Invasion: NATOization or Chinese Hegemony in Indo-Pacific. Millennial Asia.

Feeley, J. (2023, April 28). A One-Way Ticket to Irrelevance: The Dangers of Active Non-Alignment by the Global South. Global Americans. https://globalamericans.org/a-one-way-ticket-to-irrelevance-the-dangers-of-active-non-alignment-by-the-global-south/

History. (2023, July 7). NON-ALIGNED MOVEMENT (NAM). https://nam.go.ug/history

LotusArise. (2023, January 28). [Image]. Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)—UPSC. https://lotusarise.com/non-aligned-movement-upsc/

Non-Aligned Movement - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. (n.d.). https://mfa.gov.by/en/mulateral/organization/list/bc1f7d8446a445ed.html#:~:text=The%20Non%2DAligned%20Movement%20(NAM,and%20democratization%20of%20international%20relations.

NAM Members and Observers. (n.d.). Non-Aligned Movement Center. Retrieved December 15, 2024, from https://namchrcd.ir/portal/viewpage/namchrcd.ir

Taylor Fravel, M. (2023). China’s Potential Lessons from Ukraine for Conflict over Taiwan. The Washington Quarterly, 46(3), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2260141

Taran, Makar. (2020). US strategy of China’s engagement: key conceptualized regional implications. Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. https://doi.org/10.17721/2521-1706.2020.10.7

Hrubinko, A., & Fedoriv, I. (2023). China policy on Taiwan against the backdrop of the Russian-Ukraine War. Foreign Affairs, 33(1), 24-31. https://doi.org/10.46493/2663-2675.33(1).2023.24-31

Kroenig, M., & Starling, C.G. (2023). U.S. Lessons from Russia's War on Ukraine. Asia Policy, 30, 64 - 74.

Lim, K.F. (2012), What You See Is (Not) What You Get? The Taiwan Question, Geo-economic Realities, and the “China Threat” Imaginary. Antipode, 44: 1348-1373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00943.x

Norris, W. J. (2023). The Devil’s in the Differences: Ukraine and a Taiwan Contingency. The Washington Quarterly, 46(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2189343

Rajak, S. (2014). No Bargaining Chips, No Spheres of Interest: The Yugoslav Origins of Cold War Non-Alignment. Journal of Cold War Studies, 16(1), 146–179. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26924448

Rudd, K. (2021). Why the Quad Alarms China. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-08-06/why-quad-alarms-china

Sangsoo Lee. (2023). Evolution of the US’ Strategic Ambiguity in the Cross-Strait Relations. International Journal of Terrorism & National Security, (), 14-22. 10.22471/terrorism.2023.8.14

Smith, S.A. (2022). The United States, Japan, and Taiwan: What Has Russia's Aggression Changed? Asia Policy, 29, 69 - 97.

Smith, S. A. (2021, May 27). The Quad in the Indo-Pacific: What to Know | Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/quad-indo-pacific-what-know

Taylor Fravel, M. (2023). China’s Potential Lessons from Ukraine for Conflict over Taiwan. The Washington Quarterly, 46, 7 - 25.

Turner, M. (n.d.). The Global South and the Russia-Ukraine War: Nonalignment and Western Responses on the Cusp of a Multipolar World. Retrieved December 15, 2024, from https://www.securityincontext.org/posts/the-global-south-and-the-russia-ukraine-war-nonalignment-and-western-responses-on-cusp-of-multipolar-world